Death and Burial in Jordan - Pt 1

But there is no three-day period between death and the funeral as in the United States.

Everyone has seen TV news clips of an open coffin in the Muslim world, surfing along a sea of humanity in a tightly packed street, accompanied by much wailing and gnashing of teeth. Throw in shouts of “Death to America” and “Death to Israel” and you have a Mideast funeral procession.

I haven’t heard of that happening in Jordan, however.

If a person dies during the day up until sundown here, the authorities will bury them before midnight. If it is nighttime, they will lie in a hospital morgue until the next morning before a quick interment.

But there is no three-day period between death and the funeral as in the United States. No viewing of the embalmed body. No one will say, “Oh, doesn’t she look natural?” There are no funeral homes, and in the Muslim world, there is no service in the mosque proper. Gatherings for three days to comfort the family come after they bury the deceased.

The priority is to get death out of sight as soon as possible.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A MUSLIM DIES IN JORDAN?

I could write a lengthy article about the protocol for taking care of a body after a Muslim dies, but for the sake of brevity, I’ll list ten steps that take place. Bear in mind, customs differ, depending on location or sect affiliation.

1. Right After Death

As soon as death occurs, those who are present say, “Verily we belong to Allah and truly to him shall we return.” Then they petition Allah to forgive the deceased’s sins.

They close the eyes, bind the jaw, and cover the body with a clean sheet to prepare it for a quick funeral.[1]

2. Mourning

Hidaad, or mourning for a close relative, lasts three days. A widow observes a longer period of bereavement, called iddah or edda, which is four months and ten days, during which time protocol prohibits her from interaction with any man she might potentially marry. An exception would be if she had to visit a doctor. During this time, she must wear black, abstain from perfume or jewelry, and not leave the house except for work or errands. She cannot remarry until the end of iddah.[2]

This extended period of mourning does not pertain to husbands who have lost their wives, as they follow only the three days of grief.[3]

Controlled weeping is acceptable, but Islam discourages loud wailing and acting out.

3. Washing the Dead

Normally, the deceased’s family washes the body, but sometimes, they engage others to perform this rite. Only those who are Muslim and of the same sex do this, with an exception for children or spouses.

Specific rules require placing the body on a high table. Saying, “In the name of Allah,” those who wash the body with cloths, do so in this way: “upper right side, upper left side, lower right side, lower left side. Women’s hair should be washed and braided into three braids.”[4]

They repeat this a minimum of three times until the body is clean. If it needs further cleansing, the washings should be an odd number. Then, they dry the deceased and wrap him or her in a shroud.

4. Shroud

They encase the body in a white Muslim shroud, tied with three or four cords—one above the head, one below the feet, and one or two around the midsection. Protocol for wrapping males differs from that of females. The funeral begins as soon as they complete the shrouding.

If you are truly interested in seeing how the process of preparing a body for burial unfolds, here is a 38-minute video of a demonstration.

5. Funeral Prayer (Alaltul Janazah)

There are two parts spoken aloud. Then, the mourners gather and pray silently for Allah to have mercy on the departed. This happens outside the mosque in a prayer room, a study room, or in the mosque’s courtyard. There is no wake or public viewing of the body before the funeral.[5]

6. The Funeral

Everyone faces Mecca (Quiblah) while standing in three horizontal rows. Men in front, children behind, and women at the back. They silently recite the Fatihah (the first section of the Quran), asking for Allah’s mercy and guidance. Afterwards, there are four more prayers (Tahahood), before which the people say, “Allahu Akbar,” God is good.

7. Transporting the Body

The funeral procession takes place in silence, with four men carrying the deceased. Islam does not allow singing, loud crying, incense, candles, or reading the Quran during this time.

Tradition states a Muslim’s interment should be where he or she died. If that was in another country or remote location, they should be buried there, not transported back home.[6]

8. Burial Traditions

Tradition allows only men to be present at the burial, though some communities permit all mourners, including women, at the gravesite.

Notably, when King Hussein died (the father of the current Jordanian king, Abdullah II), his American-born wife broke protocol and stood in a courtyard about 100 feet from the grave. Women---even wives---are barred from the burial rites. In some communities, however, modern sensibilities are allowing women at the gravesite.[8]

Custom dictates the grave be dug perpendicular to Mecca, with the body placed on its right side facing the holy city. Those laying the deceased to rest recite, “In the name of Allah and in the faith of the Messenger of Allah.”

Islam does not allow burial casket or coffins. However, some people have told me if a person wants a coffin here, they can order one from carpenters in Herafiyah, the industrial section of Aqaba. Those helping with the interment line the bottom of the grave with a layer of wood or stones. Then they lower the body onto them and put another layer on over it to prevent direct contact with the dirt that will cover them. Each mourner tosses three handfuls of soil into the grave.[9]

You can see how quickly the whole process unfolds. If someone died unexpectedly early in the day, they could be in the grave before the evening meal. Not much time for survivors to process the death.

9. Marking and Visiting the Grave

A small nondescript marker is allowed so the family can locate the burial spot.

Minimalism and deference are the hallmarks of a Muslim cemetery. No extravagant grave markers. In fact, the family normally can’t put anything on or around the resting place, not even flowers.

“There is some debate about whether women can visit the grave of a loved one to remember him or her. While some Muslims say that this is forbidden, others think it's OK to occasionally visit the grave site [sic] to remember the deceased and meditate on mortality.”[10]

10. Consoling Family and Friends

Mourning is a significant thing in this culture. The three-day period, called azza, is a time when a person who has any connection to the family is obligated to visit and perhaps bring food. The frequency of paying condolences in daily life in Jordan is such that, “it is the azza—not the wedding or any other social event—that is the main center for gossip, networking, matchmaking, and political debates.”[11]

“If a relative of an in-law, friend, co-worker, neighbor, or acquaintance dies—no matter if it is a parent, cousin, or a distant aunt thrice removed—it is a duty to demonstrate support and show up during the azza, even if just to express your condolences, sit for a few minutes, eat a date, and leave.”[12]

Men and women gather in different places. After the burial, the men go to a rented hall called a diwan. The women assemble in the home of the closest relative of the deceased.

Everyone checks the obituaries each morning before even reading the news or sports because paying respects at an azza is of utmost importance. There is even an app for that.

Wafiyat (obituaries) is a free directory that “allows users to post and read death notices from anywhere in the world. People can search a family or tribal name, home province, town, or date, allowing them to determine how many days are left to express their condolence in person. The app provides a list of caterers, restaurants, and other service providers that may help in arranging funerals and azzas.”[13]

You can even set a watch notification for “a certain family name so you can be notified if anyone in that group dies. It is a vital way of maintaining ancient social duty in the twenty-first century.”[14]

If a person inadvertently misses an azza, “it will cause an awkward situation and may lead to long-term social isolation within the community.”[15]

I have made no secret of my aversion to coffee and tea and how that causes difficulties for me. It concerned me to read: “Coffee is offered, and it’s a must to partake…. There is a well-dressed waiter, hired of course, who circulates with a tray of coffee for the guests. You cannot say, ‘Thank you, I don’t drink coffee.’ You have to drink it. If you don’t drink it, it’s a serious insult to the deceased.”[16]

This article is a sparse summary of funeral customs in Middle East Muslim countries. But it gives you a peek into something that reveals the differences between western and eastern burial traditions.

Next week, I’ll tell about how Arab Christians handle death and burial.

[1] “Muslim Funeral Traditions,” https://www.everplans.com/articles/muslim-funeral-traditions, (Accessed September 12, 2022).

[2]Ibid.

[3]Better Place Forests, April 7, 2022. https://www.betterplaceforests.com/blog/articles/the-complete-guide-to-islamic-burial-practices-and-funeral-customs (Accessed September 12, 2022)

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6]Becky, Striepe, “10 Muslim Funeral Traditions,” https://people.howstuffworks.com/culture-traditions/funerals/10-muslim-funeral-traditions.htm, (Accessed August 29, 2022).

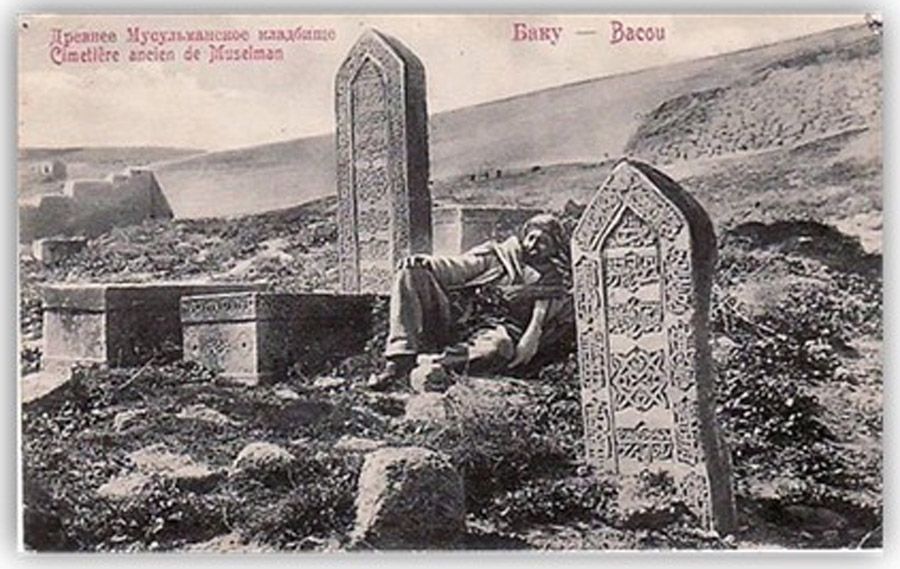

[7]https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Ancient_Muslim_cemetery_%28Baku%29. (Accessed September 13, 2022)

[8]Alia Shukri Hamzeh, “Queen Noor Mourns from a Distance,” February 8, 1999. https://apnews.com/article/30b5237677c3d6feb46c186dfeac79e8, (Accessed September 12, 2022),

[9]Better Place Forests, April 7, 2022. https://www.betterplaceforests.com/blog/articles/the-complete-guide-to-islamic-burial-practices-and-funeral-customs (Accessed September 12, 2022)

[10] Becky, Striepe, “10 Muslim Funeral Traditions,” https://people.howstuffworks.com/culture-traditions/funerals/10-muslim-funeral-traditions.htm, (Accessed August 29, 2022).

[11] Taylor Luck, “In Jordan, mourning matters. This app keeps funeral goers on task.” The Christian Science Monitor, November 19, 2019. ”https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2019/1120/In-Jordan-mourning-matters.-This-app-keeps-funeral-goers-on-task. (Accessed on August 29, 2022).

[12]Ibid.

[13] “Funeral Customs Around the World: Jordan,” February 3, 2022. https://thefuneralmarket.com/funerals-customs-around-the-world/jordan. (Accessed August 29, 2022).

[14]Taylor Luck, “In Jordan, mourning matters. This app keeps funeral goers on task.” The Christian Science Monitor, November 19, 2019. ”https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2019/1120/In-Jordan-mourning-matters.-This-app-keeps-funeral-goers-on-task. (Accessed on August 29, 2022).

[15]“Funeral Customs Around the World: Jordan,”https://thefuneralmarket.com/funerals-customs-around-the-world/jordan, February 3, 2022. (Accessed August 29, 2022).

[16]Sami A. Hanna, “Death and Dying in the Middle East,” BYU Religious Studies Center, https://rsc.byu.edu/deity-death/death-dying-middle-east. (Accessed August 29, 2022).