Little City, Big History - Part 3

All Scripture quotations from English Standard Version (ESV)

A New Discovery for Me

As I researched information about Aqaba’s history for the first two parts of this series, I discovered an archeological site I knew nothing about. It’s called Tell el-Kheleifeh (ca-LEAF-uh), an Arabic word that is related to caliph. It means “successor” and came into being after Mohammed’s death when his father-in-law and friend Abu-Bakr succeeded him as the leader of Islam. The designation stayed in use throughout all the Islamic dynasties until the Turkish Republic abolished it in 1924 after the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

As an aside, President Erdogan of Turkey has aspirations of becoming caliph over all Islamic countries again.

I haven’t been to the dig, which is halfway between Eilat, Israel, and Aqaba, twenty feet from the neutral zone between the two countries. Since they built a military installation there a few years ago, no one can visit or even take photos of the site. They are extremely strict about border and armed forces procedures. It is against the law to take a photo of any government building.

Solomon’s Presence in This Area

The Bible gives us a few tantalizing clues about this area being a place where King Solomon had control. I mentioned this briefly in part two of “Aqaba’s History.” We find an account of this story in 2 Chronicles 8:16-18:

Thus was accomplished all the work of Solomon from the day the foundation of the house of the LORD was laid until it was finished. So the house of the LORD was completed. Then Solomon went to Ezion-geber and Eloth on the shore of the sea, in the land of Edom. And Hiram [king of Tyre] sent to him by the hand of his servants’ ships and servants familiar with the sea, and they went to Ophir together with the servants of Solomon and brought from there 450 talents of gold and brought it to King Solomon.

Later, we see King Jehoshaphat (yeh-ho-sha-FAHT) trying to follow in Solomon’s footsteps. He “made ships of Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold, but they did not go, for the ships were wrecked at Ezion-geber.” 1 Kings 22:48

We know Solomon also had copper mines at Timnah, Israel, about nineteen miles north of Eilat not far from Ezion-geber/Aqaba. So, I wanted to find out if the ruins of Tell el-Kheleifeh had anything to do with these copper mining ventures. I heard rumors from some of the people I know here that the king’s mines were north of town near the airport, visible from the road. I had never seen them, but, then, I didn’t know where or what to look for.

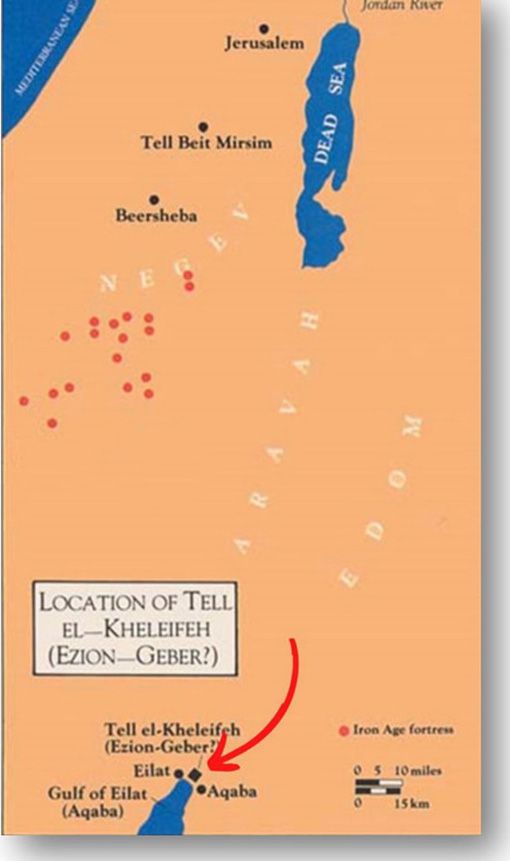

What I discovered was the work of two or three archeologists who have explored and partially excavated the site. It’s not near the airport. Here is a map from Biblical Archeology Review. I have added a red arrow to pinpoint the location between Aqaba and Eilat, right up next to the border.

Jordan Rift System/Jordan Rift Valley

The story of investigating this site begins in 1933, when German explorer Fritz Frank surveyed the Aravah (ar-ah-VAH), the depression running between the bottom of the Dead Sea and the top of the Gulf of Aqaba/Gulf of Eilat. It is part of the Jordan Rift Valley, a portion of the East African Rift System, which extends from southern Turkey some 4,000 miles to Mozambique.[1]

But I digress.

Explorers of This Area

Mr. Frank explored this site about ninety years ago, the first to do so in the modern era. As he came to the southern end of the Aravah, he happened upon a low mound about 1,500 feet from the shore of the Gulf of Aqaba. It looked like just a small hill, but he saw what he called unmistakable signs of ancient human occupation and decided to investigate. He identified Tell el-Kheleifeh as biblical Ezion-Geber.[3]

“In 1937, the American rabbi and archaeologist Nelson Glueck (GLU-eck), then with the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, led a surface survey in Transjordan, including an examination of the mudbrick remains exposed on the surface of Tell el-Kheleifeh. Based on the potsherds he picked up on the surface, Glueck concluded that the site had been occupied between the tenth and eighth centuries B.C. [between the 700s and 1000s B.C.] This fits nicely with the biblical references in Kings and Chronicles. Solomon ruled between about 970 B.C. and 925 B.C.”[4]

The last biblical reference to Ezion-Geber was in 2 Kings 8:20-22 and 2 Chronicles 21:8-10 telling the story of King Jehoram (yeh-ho-RAHM) trying to reassert Judean authority over Edom in this region.

Mr. Glueck directed three excavations from 1938 through 1940 and revised his earlier chronology to between the eleventh and fifth centuries B.C. (400s through 1100s B.C.) He changed his mind on a few other things as well, but he clung to the belief the site was Ezion-Geber.

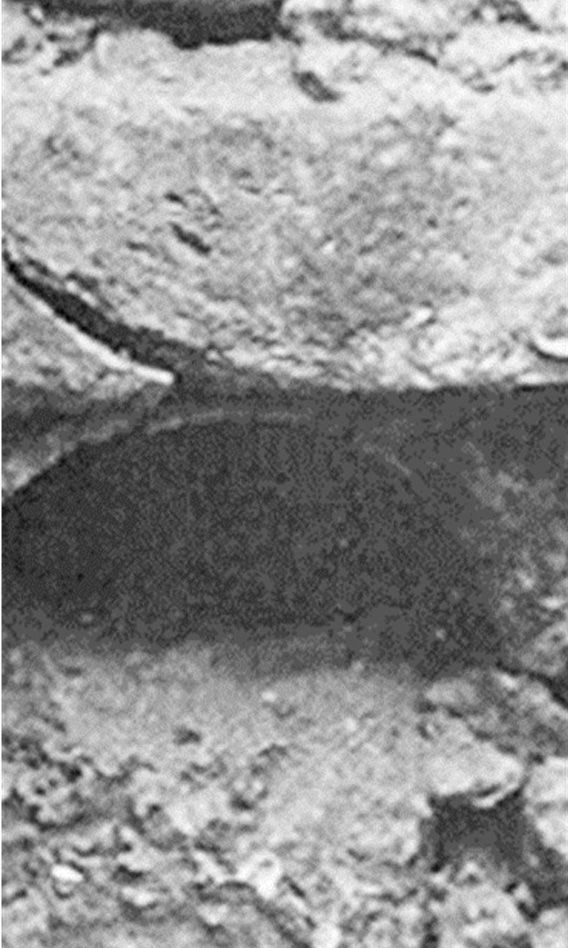

Originally, he thought the ruins were a copper-refining plant. Apertures in the walls led him to believe they were flues, so placed as to take advantage of the strong north winds that often blew through this region. This would help in processing the copper ore. However, through the work of others, he changed his belief to show that originally, the walls were constructed of wooden-beam lattices, then plastered and coated with mud. When a fire broke out, the beams were consumed, leaving holes in the walls.

Gary Pratico, later working the site himself in the 1980s, said, “The irregular holes probably held the wooden beams that were part of the interior wall lattice. But the occasional half-circle-shaped holes may have served a ventilation function, providing a flow of fresh air into the mudbrick building, especially to those rooms that contained hearths or ovens. At present, no conclusive explanation of the holes is possible, but they are best explained by the theory of interior wooden wall supports. One thing is clear: the building was not a smelter.”[5]

Glueck, himself, before he died in 1971, came to the conclusion the site was not a place where copper was processed. In 1965, in a paper presented to the Jewish Institute of Religion at Hebrew Union College, he said, “We believe now, as Rothenberg has suggested, that this structure with its purposely high floors was also designed and used as a storehouse and/or granary, and that the site, whether actually Ezion-geber or a suburb or satellite of Ezion-geber, belonged in a comparatively modest way to the type of fortified district and chariot cities which Solomon built in elaborate fashion at Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer. (I Kings 9:15-17, 19)”[6]

Another Israeli archeologist, Yigal Shiloh argues this building and others similar, possibly were citadels. But as Pratico says, “In short, we simply do not know the specific use to which this building was put.”[7]

Ezion-Geber or Not?

He goes on to affirm, “Nelson Glueck was a pioneer. He led the way into the wilderness and prepared it for those of us who followed. His surveys and excavations remain the paradigm. His studies and articles remain the focal point for the study of the archeology and historical geography of the Negev and Transjordan.”[8]

Glueck didn’t waver in his support for the tell between Israel and Jordan being Ezion-Geber. Pratico ends his article by asking, “In short, is Tell el-Kheleifeh Ezion-Geber?”

He went to say, “Glueck’s interpretation of the site was unfortunately based on a Biblical framework for which there was no archeological justification. The archeological data were made to conform to the historical contours provided by the Bible. Glueck’s identification of the site as Ezion-Geber remained the underlying premise of his interpretation of Tell el-Kheleifeh’s stratigraphy and architecture, and ultimately for its occupational history.

“Tell el-Kheleifeh must be allowed to tell its own story in its own language. For the moment at least, based on the available archeological data, Tell el-Kheleifeh cannot be identified as Ezion-Geber. This does not detract from Glueck’s achievement, but simply recognizes how far we have come in the last 50 years.”[9]

Search for Truth

Maybe there is no archeological justification and maybe there is. Ironically, most Israeli archaeologists tend to fall on the atheist/agnostic side of things. At times, they seem determined to prove the Bible and its stories are fairy tales, a lovely book of fiction. In recent years, many digs are revealing the Bible’s accounts to be true. I don’t think people with an agenda (pro-God or anti-God) should ever claim they are using a scientific method to come to their conclusions. If you start with a pre-determined outcome, that’s what you’re going to find. On the other hand, if you are searching for truth, you’ll discover it, too.

Indiana Robertson

With literally hundreds of untouched archeological sites in Israel and Jordan, it seems little Tell el-Kheleifeh is not on anyone’s radar. I may have to rustle up a trowel, a brush, and a fedora and strike out on my own under cover of darkness. I wonder if Udemy has an online course in Middle East Excavation 101?

Just kidding.

[1] https://www.britannica.com/place/East-African-Rift-System. Accessed 10/23/2022

[2] Bonne, “The East African Rift System”

[3] Gary D. Pratico, “Where Is Ezion-Geber? A Reappraisal of the Site Archaeologist Nelson Glueck Identified as King Solomon’s Red Sea Port,” September/October, 1986 Issue, https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archeology-review/12/5/6. Accessed 10/20/2022

[4] Pratico, “Where is Ezion-Geber?”

[5] Pratico, “Where is Ezion-Geber?”

[6] Nelson Glueck, “Excavations at Tell el-Kheleifeh,” https://www.bible.ca/archeology/bible-archeology-exodus-kadesh-barnea-ezion-geber-nelson-gluecks-tell-el-kheleifeh-1965ad.htm

[7] Pratico, “Where is Ezion-Geber?”

[8] Pratico, “Where is Ezion-Geber?”

[9] Pratico, “Where is Ezion-Geber?”