All Tapped Out

Jordan must have been on vacation when natural gifts were passed out to the nations of the world.

Its surrounding Muslim brothers are often awash in oil fields. But not little Jordan. It does have high-quality oil shale deposits underneath 70% of its land and several memoranda of understanding with a collection of international companies to extract the oil. But I could find no record that it has moved forward with that.

Precious stones and minerals lie hidden beneath the deserts of Iraq, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. Jordan has phosphates and potash.

Even though water is a scarce commodity in all of the Middle East, Jordan is one of the most water-scarce countries in the world. Israel, although a neighbor more than a brother, has a water surplus and has taught many other countries to use its methods of recycling and desalination for best water use. See this video for how it has achieved this.

The average Jordanian citizen—half of whom reside in the capital city, Amman—has access to less than 200 cubic meters of fresh water per year. This is in contrast to the average U.S. citizen, who has more than 9,000 cubic meters.[1]

When we visited Aqaba, we noticed water trucks driving around the neighborhood. According to a friend who lives there, “Water is delivered through pipes from the city (similar to the U.S.). The tanks on the roofs are where the water is brought in from each person’s street pipes that come into each property. The tanks store water and also feed the water through a gravity system into each home’s pipes. Each person’s home has their own water meter, like the U.S. The city reads the meter and charges quarterly.”

He went on to say different cities in Jordan shut off the water supply as a conservation method. Aqaba is fortunate because its water is shut off only half a day a month. Amman and other high population centers in the north go without water two days a week.

So, instead of a municipal water tower, every family has its own individual tank on the rooftop. No graffiti allowed!

Where Does Jordan’s Water Come From?

Most of the major water resources in Jordan are shared with neighboring countries Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Its water comes from:

- renewable groundwater – about 51%

- renewable freshwater sources (including some coming from Israel under the 1994 peace treaty agreement) – about 28%

- non-renewable aquifer (fossil) groundwater – about 9%

- treated wastewater – about 12%

The country’s three main rivers, the Jordan, Yarmouk, and Zarqa are a major part of the country’s surface water system. But Israel’s dams on the upper Jordan River and over-pumping have diminished the flow. The forty-five Syrian dams upstream on the Yarmouk—built in defiance of the agreement with Jordan—have directly affected water availability and quality in the Hashemite Kingdom.

Historical Practices

For thousands of years, local farmers, nomadic herders, and townspeople used the main surface and groundwater sources of wadis, natural springs, oases, and hand-dug wells for their water needs.

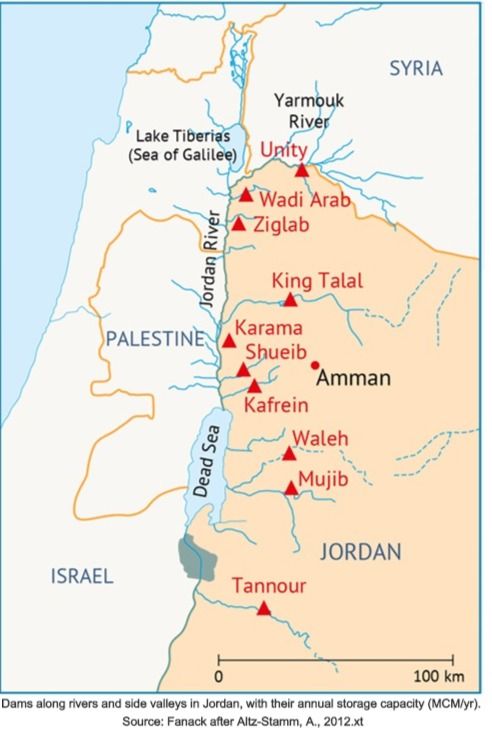

Over the last fifty years, the government has built underground cisterns to harvest and store water and rainwater. It constructed 28 dams and artificial pools to capture and retain water from the wadis to use throughout the year. Even the water used in mosques for washing before prayer was saved and recycled for use in gardens. Recently these methods have been revisited and set up in a more systematic way.[2] Thirty wastewater treatments, which are now working at over-capacity, do not do a very good job as we shall see.

Dams along rivers and side valleys in Jordan, with their annual storage capacity (MCM/yr). Source: Fanack after Altz-Stamm, A., 2012.

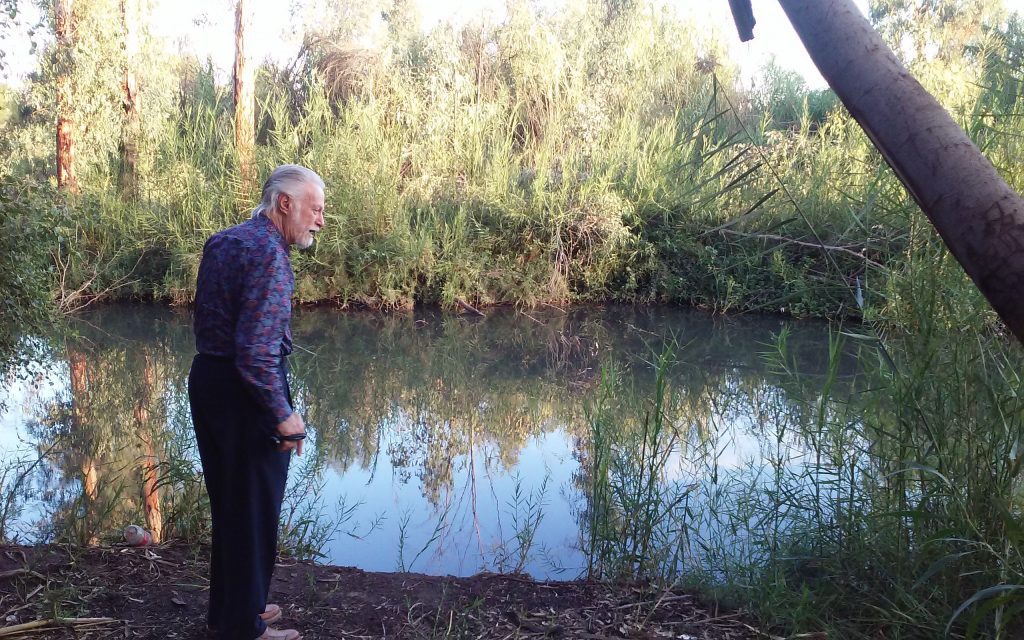

In the past, one of the main water resources in the Hashemite Kingdom was the Jordan River. However, in 1953 after Israel built the National Water Carrier—a concrete pipeline, canal, and reservoir system carrying water from the Sea of Galilee to the rest of Israel—the flow of the Lower Jordan River dropped significantly. This PBS video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=taMWUjda3fA reports the Jordan River is down 95% from its historical level. The water that Israel provides from the Sea of Galilee as part of the 1994 peace treaty was meant to compensate for this loss.

Here is a picture I took near the headwaters of the Jordan. It was more like a creek than a river.

Water Quality

A recent study of water quality in Jordan found that:

- About 70% of spring water is biologically contaminated.

- Water resources have a significant level of toxicity.

- Industrial discharges are improperly treated or untreated.

- Extracting too much groundwater for irrigation has reduced the water table in some aquifers and tripled salinity.

- Unregulated fertilizer and pesticide application have increased nitrates and phosphorus in water supplies.

Water Usage

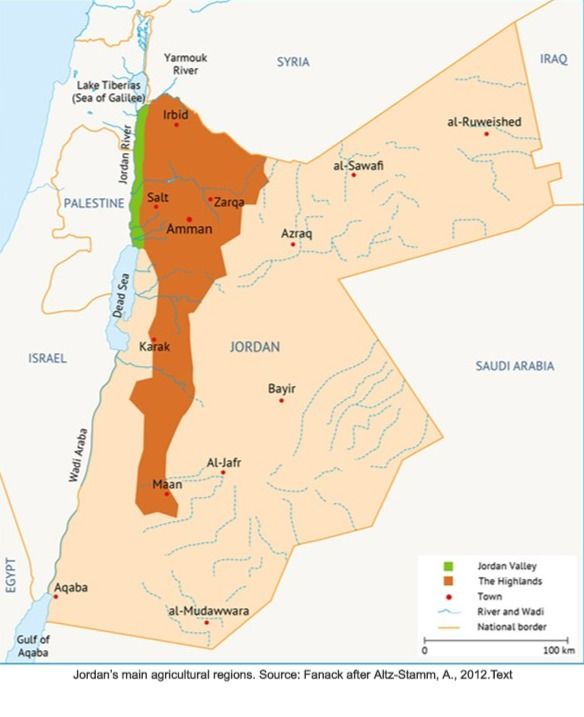

Population centers generate most of the wastewater, and treatment plants, located near these cities, release the water into watercourses on the ridge of the Jordan Valley. Here it flows into the valley for use in irrigation, which can only be applied to certain crops, because farmers often misappropriate it before it has been diluted with fresh water for use in the produce fields.

About three quarters of treated wastewater is used in the agricultural sector.

Reasons for Water Problems

While Jordan has very little rainfall, there are more reasons than that for its dire water problems.

- Refusing to comply with government regulations, farmers pull the wastewater out of the Zarqa River upstream before it is mixed with the fresh water, posing a health risk to those who consume their produce.

- Illegal extraction of treated wastewater downstream of the al-Samra treatment plant. The wastewater flows down the Zarqa River to the King Talal Reservoir, where it is mixed with fresh water and released downstream to the Jordan Valley for crop irrigation.

- The huge influx of refugees from Syria and Iraq has resulted in a sharp increase in wastewater, which is collected in open ponds and illegally dumped upstream of the treatment plants. They also contribute to an uptick in water consumption.

- Even more alarming, “half of Amman’s water supply is ‘lost’ or unaccounted for somewhere in the nation’s distribution network through leakage, under-registration, and theft in municipal water supply,” according to USAID.[3]

Consumers in Jordan have attacked and injured water distributors and meter readers, demanding extra rations.

But USAID reports that “two-thirds of the Kingdom’s water goes to low-value agricultural crops, while higher value demands for urban consumers, industry, and tourism go unmet.”[4]

Aqaba has always enjoyed plenty of this life-giving liquid thanks to abundant gravity-fed water supply from the Disi Fossil Aquifer in the highlands above the coastal city.[5]

How to Fix the Problem

Everyone knows the causes of the water problems in Jordan. The issue comes with doing what will fix them.

This is what has to be done to bring the water issues under control:

- Effectively treat biological and toxic contaminants at the source

- Regulate and enforce the quantity and materials of crop fertilization as well as wastewater treatment before discharge

- Prevent over extraction of groundwater

- Improve wastewater treatment

Of course, Jordan wants more water from Israel. When the 1994 agreement was signed between the two countries, Israel was in a water-deficit situation as well. From the development of desalination plants bringing water from the Mediterranean, Israel has moved to a surplus. This is a fascinating story. You may be interested in the PBS program “How Israel Became a Leader in Water Use in the Middle East.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=taMWUjda3fA

Current Plans to Get More Water

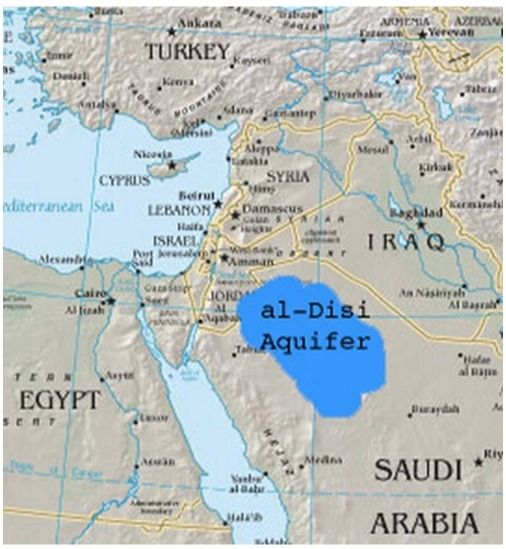

The two main projects to increase Jordan’s freshwater supply are the Disi Aquifer Water Conveyance Project and the Red Sea-Dead Sea Project.

The Disi Project transports water to Amman and other Jordanian cities from the Disi Aquifer underneath the southeast border with Saudi Arabia, which also extracts water from this resource. There is currently no water-sharing contract between them, only a gentlemen’s handshake.

You may recall from my last blog post about organic farms that Wadi Rum’s green polka-dot fields draw from this water beneath their roots.

I wonder if all the water Yehovah provided the Israelites during their forty-year trek in this area came from Heaven or from the Disi Aquifer?

While classified as a fossil aquifer (a large underground reserve of water established under distant climatic and geological conditions), it is actually replenished at an annual rate of about 50 MCM (million cubic meters) per year. Only about ten percent of the aquifer lies in Jordan, however.

Construction of the Disi Project began in 2009 becoming operational four years later at a cost of about $1.1 billion. Since then, the Disi water conveyance has transported about 100 MCM a year to Amman and Aqaba. It is expected to provide Amman with 100 MCM a year until at least 2022.

VIDEO: How Does an Aquifer Work? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nOe9cGo15_U

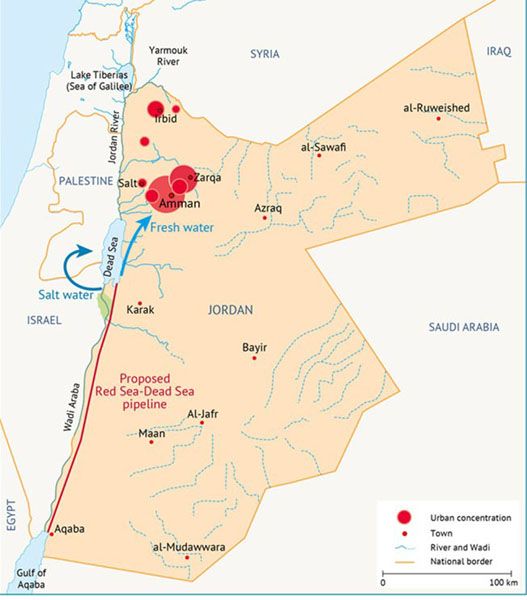

Red Sea-Dead Sea Project

The proposed Red Sea-Dead-Sea Project https://water.fanack.com/specials/red-sea-dead-sea-project/ could become a new source of surface water by transferring water from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea through a series of pipelines, providing fresh water to Israel and Jordan via desalination processes, while recharging the Dead Sea with concentrated saline water.

VIDEO: Red Sea-Dead Sea Project https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31dRNOcaOXQ

Video: The Politics of Water (Al Jazeera broadcast) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wP373SD3Ou8

Jordan’s only access to the sea is at the Red Sea Port of Aqaba. This town has no immediate need for seawater desalination, as it currently gets its water from the Disi Aquifer. But the government plans to implement a major desalination and water transfer project here. In 2013, Jordan signed an agreement with Israel and Palestine for the joint implementation of the Red Sea-Dead Sea Project.

In February 2015, Jordan and Israel signed an agreement to implement the first phase of the project at a cost of $900 million over a period of three years. This first phase includes the construction of the Aqaba plant and a 112-mile pipeline between the Red Sea and the Dead Sea.

The plant will initially produce around 80 MCM a year of fresh water. Israel will purchase 40 MCM a year for use in the area of Eilat and the Aravah Valley. The rest of the fresh water will be available to the city of Aqaba to reduce its reliance on the Disi Aquifer. As part of the agreement, Israel will sell Jordan an additional 50 MCM a year of fresh water from the Sea of Galilee, which will be transferred for use in Amman.

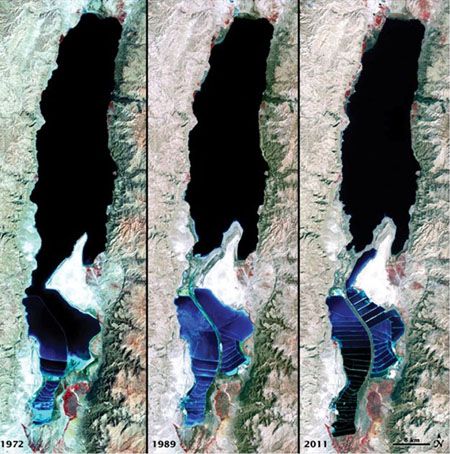

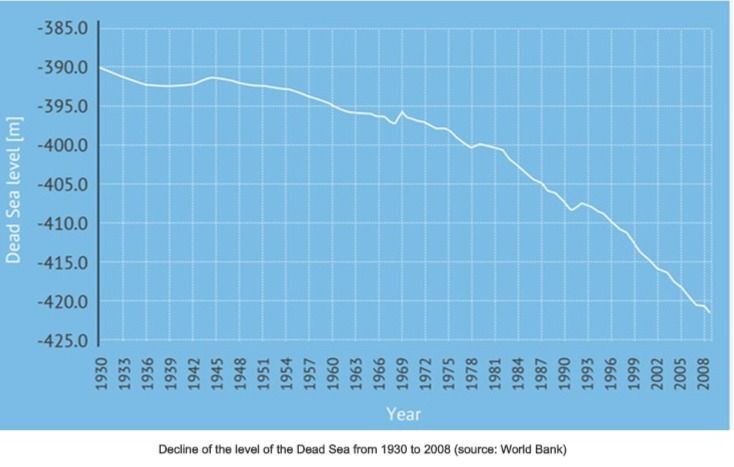

The pipeline to the Dead Sea will initially transport brine (highly concentrated saline water), a by-product of the desalination process. This will ostensibly serve to rehabilitate the Dead Sea, which has been shrinking for the past 30 years. As the desalination plant in Aqaba expands, up to 2,000 MCM/yr of brine could be pumped to the Dead Sea in the future.

Advocates of the project consider this an innovative solution to save the Dead Sea, but critics worry about mixing the brine of these two bodies of water. They have very different mineral contents, and environmental experts are concerned that the addition of Red Sea brine will alter the composition of Dead Sea water.[6]

While I am grateful that Aqaba does not have the same water concerns that Amman and other large population centers do, I know Al and I will have to diligently work on improving water conservation. We will be moving from a rural paradise receiving a lush 42 inches of rainfall a year to this seaport city where 1.3 inches is the average. I won’t have a dishwasher, and our clothes washing machine will be different. The toilet bowl will be almost bereft of water. And iced drinks are a little unusual. No free water at restaurants.

NOTE: Updated to 2021 when we arrived in Aqaba and moved into our new apartment. We have a brand-new dishwasher and clothes washer. Our water bill in the last year has averaged less than $10 a month. I am flabbergasted!

Just one more area in which we will have to shift paradigmly.

For the next three weeks, my sweet husband will be a guest blogger, giving me a little time off. The subject to look forward to on June 25 will be transportation in Jordan. I think you’ll enjoy it.

Anita

[1] https://www.theglobalist.com/jordans-dry-times/

[2] https://water.fanack.com/jordan Accessed 06/08/20

[3] Jordan Water Sector: Facts and Figures (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Water and Irrigation. 2015. p. 14. Retrieved May 4,2018.

[4] https://www.theglobalist.com/jordans-dry-times/

[5] Ibid. Wikipedia

[6] Ibid., Fanack.com