MARHABA—Hello and Welcome!

Ahlan wa Sahlan, marhaba, hello, and welcome follow you all over Jordan.

While ahlan wa sahlan is usually translated, “welcome,” the phrase comes from the Arabic words for family and comfort, so “relax and make yourself at home” might be a better way to translate it.

In a country where shame and honor are of utmost importance, Jordanians believe it is shameful not to treat visitors to their country as they would in their home.

Jordan is a place filled with wonders, scrumptious food, beautiful geographic sites—everything from green fields and mountains, to desert and sea. But the aspect most people remember from their trip to this land is the warmth, sincerity and genuine hospitality of its people.

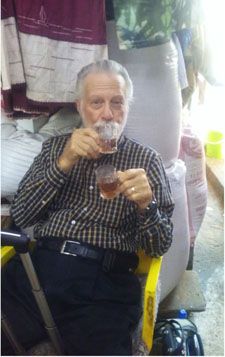

Westerners are sometimes taken aback by such open friendliness. Visiting a store often brings an invitation to chat and have tea whether you buy anything or not. When Al and I asked our friend to drop us off at a spice store in the souk of downtown Aqaba, the shopkeeper immediately handed us a cup of tea.

Unfortunately, I have never been a fan of coffee or tea. I am going to have to find a way to get around this prominent part of Arab hospitality without offending anyone. I carried my cup around and pretended to take sips. Then I set it down behind a pot. Al picked it up and savored it on my behalf.

It is not unusual for a Jordanian to invite you, a stranger, to eat in their home. A “Jordanian invitation” means that you are expected to bring nothing and eat everything.

If you’re invited and you don’t want to accept, a broad smile with your head lowered, your right hand over your heart and “shukran shukran” (“thank you, thank you”) is a clear, but socially acceptable, no. You may have to do this several times. It’s all part of the social ritual of polite insistence.

A core aspect of Jordanian culture is hospitality. This rule of taking care of guests. The social rule of taking care of the guest flows from ancient Bedouin tradition. It is rooted in the harsh environment of many parts of the Middle East where it was a moral requirement to provide all travelers with food and water. It is taught from the cradle and has earned Jordan great respect in the hospitality arena.[1]

One thing you should take note of is not to compliment the lady of the house on anything in her home. They are duty-bound to give that item to you. That is one reason why their guest rooms are sometimes sparse.

Our host told us a story of how an American tourist visited the Arab community at Wadi Rum. Our host was a long-time friend of the Arab, so the tourist automatically was as well. When the tourist made a comment of how much he like the dishdash—the long white shirt Bedouins sometimes wear—the Arab gentleman took him to town and asked his tailor to measure the American and make him his own dishdash (also called dishdasha).

These customs have persisted even as times have changed, and love of travelers is still a prominent characteristic of Jordanian culture.[2]

PERSONAL SPACE

Personal space doesn’t exist in Arab culture. This is disconcerting for most Westerners. Arabs in general, and Jordanians in particular, are curious and genuinely want to know about other. We might even consider them nosy.

Standing in or forming a line is a foreign notion because Jordanians tend to ignore an form of organization. In many situations hanging back courteously is an invitation for other people to move in front. However, on the rare occurrence there is a line, they abhor anyone disrespecting it. But they will do it themselves![3]

Sitting alone soaking up the day, you may find someone coming up to you eager for a chat. It can be difficult, if not impossible, to convey your desire to be alone.

Westerners are more used to sidestepping strangers and shopping quickly often come across as cold. Smiling, learning one or two of the standard forms of greeting, acknowledging those who are welcoming you and taking the time to exchange pleasantries will bring you closer to people more quickly than anything else.[4]

People shake hands in Jordan much more than in the West, and even the merest contact with a stranger is normally interspersed by at least one or two handshakes to show brotherhood.

One afternoon, Al and I decided to take a short walk to a grocery store five blocks away. As we strolled along the perilous sidewalk, I took pictures of the beautiful homes and entry gates and tiles outside the buildings. I was trying to get a clear shot of a striking entryway when a man and little girl walked by. He asked if we needed help—a common question in Jordan. We struck up a conversation. “Where you from?” He was very surprised we were in a neighborhood. He said, “Most tourists go to the hotels or beach. They don’t come here where we are.” He was extremely cordial, and we have found it so with everyone we have encountered here.

Even after we got to the little shopping area, we saw a taxi driver changing a tire. When he saw us, he got up and walked over to greet us. He did not have a good grasp of English, but somehow he and Al communicated. He knew the word “welcome”.

As we came back and turned onto our block, the little boys who play soccer in the street every evening after school asked Al if he wanted to kick the ball. He said, “I’ll try.” He kicked it, and a boy said, “Bravo!”

BEDOUIN HOSPITALITY

There is only one country in the world where Palestinians can become citizens. Even so, there is a clear differentiation between Jordanians, Bedouins, and Palestinians.

- Bedouins are considered to be the purest Arab stock.

- Jordanians are residents who have lived east of the Jordan River since before 1948.

- Palestinians are those whose birthright extends back to areas west of the Jordan River.[5]

Bedouin culture is at the root of Jordanian hospitality.

According to Wikipedia, here are the Bedouin Honor Codes:

- Sharaf is the general Bedouin honor code for men, which includes protection of the women of the family, property, honor of the tribe, and protection of the village.

- Ird is the honor code for women and more than just virginity. It is emotional and conceptual. Sexual transgression can take it away, and it cannot be regained.

- Diyafa is hospitality and requires even an enemy to be given shelter and food for several days

- Hamasa relates to courage and bravery. It is closely related to manliness and includes the ability to withstand pain.

- Poverty does not exempt one from duties.

- Generosity requires one to offer gifts which cannot be declined.

- The destitute are looked after by the community.

- Tithing is mandatory in many Bedouin societies.

The codes are falling into disuse as more Bedouins accept sharia or national penal codes as the means for dispensing justice.[6]

It is easy to see why hospitality is ingrained in the Bedouin psyche.

Bedouin culture always welcomes both friends and strangers. The first order of the day is to begin brewing coffee early in the morning to make sure they’re prepared for unexpected visitors.

STAY AS LONG AS YOU PLEASE

Bedouin culture takes receiving guests to another level, as it is customary to allow guests — whether friends or strangers — to stay as long as they please. No questions are asked by the host for up to three days; however, on the fourth day the hosts are allowed to ask you your name and what you want, but not before.[7]

Historically the Bedouin have become accustomed to the desert’s unforgiving climate. Today, however, Bedouin culture has transformed as many abandoned the harsh traditional lifestyle and joined the urban migration into modern day villages and cities.[8]

Some Bedu on the western edge of Jordan continue to live in the characteristic black goat-hair tents known as beit al-sha’ar, or “house of hair”, and still camp in the valley during winter, grazing their herds of goats, sheep or camels and move to higher plateaus to relieve the heat of the summer. Often the only concession they make to the modern world is the acquisition of a pick-up truck, mobile phones, plastic water containers, and perhaps a kerosene stove.[9]

Life is changing for the Bedu. Settlement is being driven by the desire for access to schools, medical facilities, water and electricity. They continue to travel, but they move short distances depending on the season and stay within close proximity to the school for their children and the lodge where a number of them are employed. Today they are more likely to pick a good spot for their home based on mobile phone reception rather than access to water.[10]

YOUR BURDEN IS A RELIEF TO ME

Jordanians do not feel you owe them. Your happiness is a blessing to them and they value the role they have been able to play in your life.

Jordanians will pretty much drop anything to answer someone in need of help. I discovered a new phrase recently. It translates to “Your burden is a relief to me.” It sums up the community perfectly. Whether it’s a phone call late into the night, a friend or family member they bump into on the street or a random stranger (although stranger really isn’t a term that exists here), Jordanians put priority on helping that person. Whatever plans they may have had are put to one side and no burden is too great, it is as the phrase says "a relief."[11]

JORDANIANS DON’T GO DUTCH

In Jordan, it is virtually unheard of to split the bill. I guess you could say it’s all or nothing and is often a fight to the end. Sometimes it can take half an hour arguing (in good nature and much to the amusement of those watching) about who was going to pay. Who wins? Well, it’s often the one who manages to move a little faster or distract the other.[12]

As one Canadian lady put it, “Jordanians are generally more personable than Westerners. They prefer to have coffee or tea and learn a bit more about you and your family before embarking on a business venture. I often found that we would have tea or be invited over for dinner by people with whom we did business. They would eagerly bring meals during Ramadan as well as at any other time. I have even had an experience in a shoe store where the store owner bought beverages for the children before we purchased anything.”[13]

During the three weeks we spent in the Middle East last year, Al and I found the legendary Jordanian hospitality and friendliness to be absolutely true. From experiences in eating out to shopping and simply walking down the sidewalk, the local were very warm, friendly and accommodating.

I wanted to purchase a special necklace for my cousin from a shop with handmade jewelry. The owner made it to order and threw in a pair of earrings free.

We got a discounted price from the spice proprietor I mentioned earlier because he knew our host, but I didn’t know the jeweler, and he didn’t know me. He knew I was an American and wanted to do something special for me.

RELIGIOUS AND SOCIETAL TOLERANCE

‘In Jordan, we are all neighbors and friends,” says Usama, a Jordanian tour guide. One of his favorite topics is the intersection of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Interfaith dialogue is a significant part of guide training in Jordan. He says guides should explain history from the perspective of the Old and New Testaments and the Koran. “I’m trying as much as I can to connect historical sights and stories and show the overlap where it exists,” he explains.[14]

The strong connection that Jordanians have with religion is an interesting cultural aspect. Jordan is a Muslim country where Islam is the major practiced religion. The religious experience is an individual choice that everyone enjoys in his own way.

Five percent of the population practice Christianity. Christians in Jordan are exceptionally well integrated into the Jordanian society, and Jordan Christian communities resemble Muslim communities in many ways. For instance, they are organized in tribes placing strong importance on the extended family system.[15]

Jordan has long been a haven for refugees. Refugees from Palestine, Iraq and Syria now figure significantly into the country’s population. While the mix isn’t without economic and social issues, the innate inclination to welcome strangers and neighbors while living in harmony is clear to all who visit[16]

As I have mentioned in an earlier blog, Jordan is the only Arab country to accept Syrian refugees. And that at considerable cost to its own economy and precious water resources. It seems to me that Jordan got a double dose of hospitality that I don’t see in other Arab nations.

There was much more information in my research on Jordanians, so I will add a couple more blogs about the Jordanian family and culture next time.

Anita

[1] https://www.jdtours.com/jordan/culture/

[2] https://blog.myjordanjourney.com/the-beauty-of-jordanian-people

[3] https://theculturetrip.com/middle-east/jordan/articles/10-customs-only-jordanians-can-understand/

[4] https://www.roughguides.com/destinations/middle-east/jordan/culture-etiquette/

[5] https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/jordan-visit/index.html Accessed 12/24/19

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honor_codes_of_the_Bedouin

[7] https://epicureandculture.com/bedouin-hospitality-immersing-myself-in-jordans-bedouin-culture/

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] http://www.apieceofjordan.com/importance-jordanian-hospitality

[12] Ibid.

[13] https://www.international.gc.ca/cil-cai/country_insights-apercus_pays/ci-ic_jo.aspx?lang=eng

[14] https://www.intrepidtravel.com/adventures/visiting-jordan-local-guide/

[15] https://www.jdtours.com/jordan/culture/

[16] Ibid. www.intrepidtravel.com