Death and burial in Jordan - Pt 2

As we prepared to move here and soon after we arrived, the number one question friends and family asked us was, “What will you do for health care there?”

Last week I wrote about what happens when a Muslim dies in Jordan. In this blog, I want to talk about Arab Christian funerals and the legal protocol.

When a Jordanian Christian dies, the family follows many of the same steps as for a Muslim, but there are some obvious differences.

· Christians wash the body of those who have died.

· They bury them in a shroud.

· They frown on loud mourning.

· The family covers the grave with dirt.

Some differences:

· Of course, they do not say the Muslim prayers nor turn the bodies toward Mecca.

· The funeral takes place in the sanctuary of the church.

· The departed lies in an open casket in which they will be buried, instead of being placed directly into the ground.

· The mourners attending the service pass by the coffin to pay their last respects.

LEGAL ASPECTS OF DEATH

When a person dies at home, the family must summon the doctor to declare the cause of death. If he or she had been under a physician’s care, it is a simple procedure. He then fills out a “Notification of Death.”

If there is some question surrounding the circumstances of death, authorities may order an autopsy. But normally, they prefer not to do anything they consider disrespectful to the body.

It’s a little off topic, but I discovered in research that Jewish tradition—which like Islam does not allow embalming, cremation, or anything invasive done to the body—goes so far as to place bloody clothing the deceased may have been wearing at the time of death into a bag that goes with them into the grave. The same for strands that may have come out while the preparers are brushing or arranging the hair. Everything about the person goes with them.

If a person dies in the hospital, the authorities notify the doctor treating him or her to complete the Notification of Death. The family must have this document for approval to bury the body. The next of kin takes this paper to the Ministry of the Interior within seven days. After interviewing the family to find out the personal details of the deceased, the authorities will issue a “Certificate of Death.”

At that point, the family may make arrangements for the funeral and burial.

WHAT HAPPENED TO A FRIEND

Last winter, I wrote about Dinah, a friend in our community who died of COVID in the hospital. I spoke with her family member who made the preparations for her interment. Her situation was not normal because of the pandemic. If the person has a communicable disease, the process speeds up. The authorities want them buried as soon as possible. No one notified her relatives Dinah died until the hospital had prepared her body and placed it in a body bag on the way to the cemetery. They didn’t know she was in danger of imminent death, so the shock was profound and took a while to work through. None of us in the community were aware she had passed away until the burial was over.

Besides notifying local authorities, American are supposed to inform the U. S. Embassy in Amman. Dealing with the embassy proved fruitless for Dinah’s family. There is a document called CRODA, which they are still waiting to receive eight months after starting the process.

C – Consular

R – Report

O – of

D – Death

A – Abroad

According to the embassy’s website: “The deceased’s family will need this paper for various purposes in the United States. This is especially true if the deceased has already been buried in Jordan.[1] A family member makes an appointment with [the] embassy and provides the following information:

1. Original local death certificate in Arabic with English translation issued by Jordanian authorities.

2. Original notification of death issued by [a] hospital or doctor in Arabic with English translation.

3. U.S. passport of the deceased.

4. Social Security number of the deceased.

5. Primary residential address in the U.S. and/or country of residence for the deceased.

6. Full name, address and telephone number of next of kin.”[2]

Fortunately, they had better luck with the Social Security Administration and were able to close Dinah’s account there and tie up loose ends.

CEMETERIES

There are two cemeteries near Aqaba. The larger Muslim burial ground is north of the city. I have only heard its name pronounced, so I’m unsure of its spelling—Maamba (mah-AHM-ba).

In the southeast quadrant of Aqaba, on a narrow side street close to where we live, is Shalala (sha-LAH-lah), a walled-in, locked area for a Christian cemetery and potter’s field for all non-Muslims. You must have an appointment to gain entrance.

Unlike the United States, where people may buy their plots ahead of time—even finding it advantageous—that is not what happens here. They bury a person in the next available site. No family plots either. Unless you and your spouse die at the same time, they will not inter you next to each other.

The priest of the local Greek Orthodox Church used to be the one who oversaw burials there, charging 600 JD ($846) for a plot and opening and closing the grave. He has retired, and I do not know who to contact now—not the current priest, I have been told. Perhaps the cost also includes the concrete vault authorities require since COVID. The locked fence and concrete-lined holes prevent Muslim grave-robbers and wild dogs from desecrating those buried there.

The cemetery workers always dig several holes and line them ahead of time, so there is no waiting to open a grave. A couple of people have told me bodies are not buried six feet deep, but no one seems to know the exact depth the government requires.

Here are a few other expenses associated with the burial:

90 JD ($127) – The ambulance and men to transport the body

356 JD ($502) – The stonework and filling and placing the concrete vault

25 JD ($35) – The laser-cut words on the headstone

The family picks out a piece of marble and gives the measurements to a print shop (which does the engraving). The family does not buy a blank headstone already cut a certain size. Therefore, the cost depends on which piece of marble they choose.

There is no casket/coffin store. The family must commission one from a carpenter in Herafeyeh, the industrial area north of town. There are no metal caskets lined with beautiful fabric here. They are all plain wood.

As we prepared to move here and soon after we arrived, the number one question friends and family asked us was, “What will you do for health care there?”

Honestly, we never thought about it. Since we rarely visit a doctor and take no medications, it didn’t occur to us. We were more concerned with what will take place when one of us dies. It’s a given we will be buried here. The cost to fly a corpse to America is prohibitive. Estimates start at $16,000 if there are no unusual circumstances.

MAKING PLANS FOR THE INEVITABLE

Usually when a person reaches their 50s—and certainly by their 60s—a heart-knowledge sets in. Head-knowledge has told them for years, even decades, one day they will die. Maybe it’s the death of parents or going to a high school reunion or college homecoming and realizing many friends have passed away that triggers this fact. Perhaps it’s the diagnosis of a serious illness that activates the realization the horizon of their journey on Earth is visible.

Many make funeral arrangements so their children or family won’t have to, lessening the stress for others. After the events of the last two and a half years, everyone should be considering their mortality, regardless of age.

For decades, I have desired to be buried in a white linen shroud and laid directly into the earth, bypassing a casket and concrete vault. I can’t stand the thought of turning into goo inside an airless container. I would rather return “dust to dust,” as the Creator intended. Embalming is not my personal choice. Whatever others want to do, however, is none of my business.

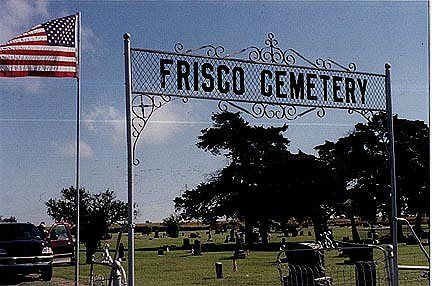

Many of my paternal ancestors are buried in a rural cemetery in Frisco, Oklahoma, where there was the possibility of realizing my burial wishes. I researched whether it was legal to forego embalming, then made my preference known to my family. Finally, I talked with a local funeral home director about what part he would have to play. Basically, he would keep me refrigerated until the interment and transport my body to the burial ground.

When the Lord called us to Jordan, I thought my wishes would fit right in. I was extremely disappointed to learn I must be buried inside a vault here.

However, I recently learned there are only sides and a top, not a bottom. If so, they can place me directly on the dirt. That will work.

So what will happen if Al or I die? For simplicity’s sake, let’s say we die in the hospital with no mystery surrounding our death, and we do not plan to be repatriated to America for burial. We will be interred within twenty-four hours.

Here are the bullet points:

· The hospital informs the doctor so he can issue a Notification of Death.

· The next of kin notifies the police and the U.S. Embassy in Amman.

· Someone at the hospital washes the body and place it in a body bag.

· Someone will dress the body in the burial garment. Ours won’t be a shroud exactly. I already made two white linen robes, which we wore at the vow renewal of our fortieth wedding anniversary. With gold thread, I embroidered the sleeves with the Scripture, “I am my beloved’s, and he/she is mine.”

· An ambulance or hearse takes us on our last ride.

· There will be a graveside service since we are not affiliated with any of the churches here. They will lay one of us to rest in the sands of Shalala at the foot of the Midian Mountains. Kind of sounds biblical, doesn’t it?

I have not verified exactly what will happen to the last one standing—Al or me. I’m still working on that. But when I get it together, I’ll blog about it. Frankly, we’re hoping to go through the Tribulation together and walk into the kingdom of God without tasting death. But if that not be the Father’s plan, we’ll face it when it comes.

I hope this has been educational, not morbid. I invite your comments below.

[1] https://jo.usembassy.gov/u-s-citizen-services/death-of-a-u-s-citizen/. Accessed 09/17/2022

[2] Ibid.