Little City, Big History - Part 2

Inhabited since around 4000 BC during the Chalcolithic (cowl-co-LITH-ic) Period, Aqaba’s strategic location for overland trade of spices and other goods between Asia and Africa strengthened its importance over centuries, especially before the Suez Canal.

HISTORY

Inhabited since around 4000 BC during the Chalcolithic (cowl-co-LITH-ic) Period, Aqaba’s strategic location for overland trade of spices and other goods between Asia and Africa strengthened its importance over centuries, especially before the Suez Canal.[1] It also became a regional hub for copper production because of its closeness to copper mines in the Sinai Peninsula, the Negev, and locally.[2]

We can look out our front gate and gaze at the Sinai Peninsula, where Asia embraces Africa.

“The city reached its peak during the Roman era and was also the garrison of the Roman 10th Legion of the Sea Strait. Aqaba was also the site of some of the adventures of Sinbad the Sailor in the famous Arabian Nights.”[3]

TIMELINE OF AQABA’S HISTORY[4]

735 – 600 BC

First the Assyrians, then the Babylonians controlled Aqaba. It was a time of prosperity.

539 – 333 BC

The next world power, Persia, defeated the Babylonians and took control of the city.

The economy continued to grow until the Greeks became its master. After the Wars of Alexander the Great, one Greek historian described Aqaba to be "one of the most important trading cities in the Arab World."[5]

64 BC

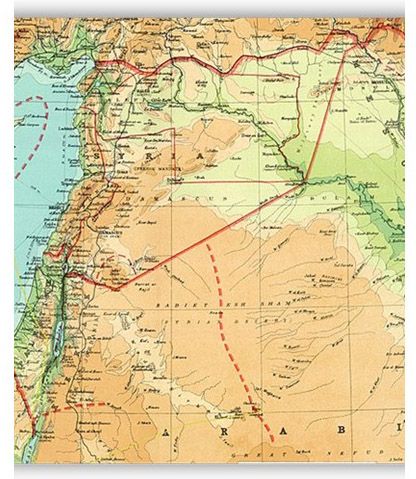

Then marched in the conquering Romans. Emperor Trajan connected the city with the “Via Traiana Nova,” the impressive network of Roman roads that joins Gaza, Petra, Madaba, Amman, Jerash, Bosra, Damascus and Palmyra.”

300 AD

The Byzantines were next and appointed “Arab Christians from South of Arabia to control the city on their behalf.”

Constructed under Byzantine rule between 293 and 303, the Aqaba Church is considered to be the oldest known purpose-built Christian church in the world.[6]We can still see the ruins near downtown.

650 AD

The nascent Muslims blazed their way through this part of the world and were the next in control. They built another city, known as Ayla, outside the walls of the Roman city Aila---leaving it to decay---to serve those on their pilgrimage to Mecca.

Ayla took advantage of its key position as an important stop on the trade route to India and Arab spices (frankincense and myrrh) between the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian Peninsula.[7]

In 1068, a powerful earthquake destroyed the city and sent its economic importance into oblivion.[8]

“Baldwin I of Jerusalem took over the city in 1115 without encountering much resistance. He moved the city center 1,600 feet south along the coast and built a crusader fortress he called Elyn (EH-lin). This allowed Jerusalem to dominate all roads, “between Damascus, Egypt, and Arabia, protecting the Crusader states from the east and allowing for profitable raids on trade caravans passing through the area.”[9]

“The garrison of Elyn (now serving primarily as a military outpost) was further strengthened in 1142.There was no large-scale settlement of Europeans in the area, and the region between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba remained mainly inhabited by Bedouins, who were obliged to pay tribute to the Lordship of Oultrejourdain.”[10]

What in the world is the Lordship of Oultrejourdain?

I’m glad you asked. I never heard of it either, but here is what Wikipedia had to say:

“(Old French for "beyond the Jordan," also called Lordship of Montreal) It was the name used during the Crusades for an extensive and partly undefined region to the east of the Jordan River, an area known in ancient times as Edom and Moab. It was also referred to as Transjordan.”[11]

Perhaps a better term would be “Principality of Jordan.” It had to do with this loosely define area under the control of Baldwin I. Few Christians lived here. Mostly populated with Shia Bedouin, everyone was assessed tax. Like everything else, this was all about money. Jordan was in the spice caravan trade routes, and there was money to be made by taxing all the goods that came through.

1116 AD – 1250 AD

In the 12th century, the Crusaders captured the city. They built a fort on Faroun Island, 7 km (4 miles) offshore. “Despite all efforts to fortify the region, the city was captured in 1170 by a squadron sent by Saladin (sah-lah-DEEN) as he was besieging Gaza; it was never retaken by the Crusaders.”[12] The Ayyubids and Saladin controlled Ayla and the island, and the fort became known as Saladin’s Castle. In 1250 AD, the Mamluks took over and built their fort on the Island.

1917 AD

The Ottoman Empire took control of the area, until 1917, the time of World War I, the great Arab Revolt, when the Arabs drove out the Ottoman Turks with the help of England and France, and Britain created the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan by a mandate.

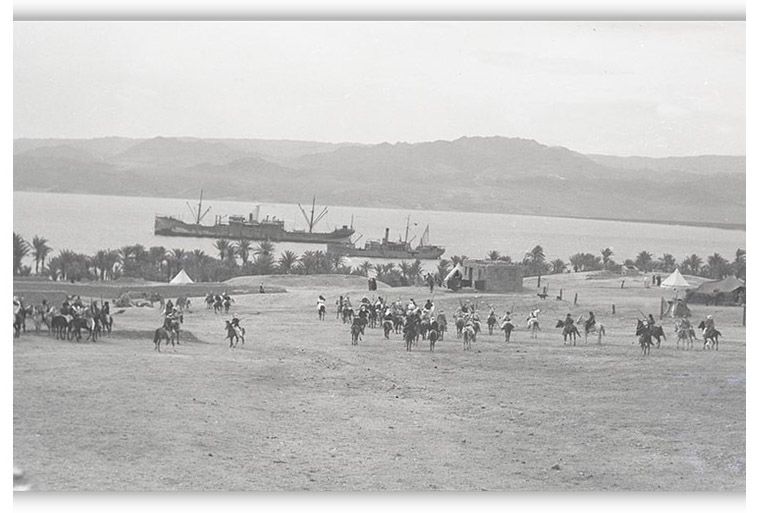

Aqaba became a major Royal Navy depot, supplying and transporting Feisal's forces upon his arrival on 23 August.[13]

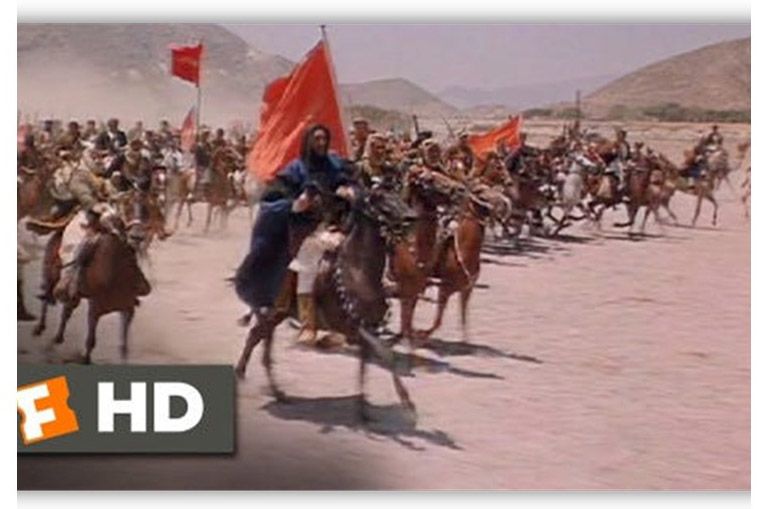

In twentieth-century history, everyone connects the city with T. E. Lawrence and the July 6, 1917, Battle of Aqaba. It was one of the key battles in World War I to break the Ottoman Empire's hold over the Middle East. If you have never seen Lawrence of Arabia, the movie, click here.

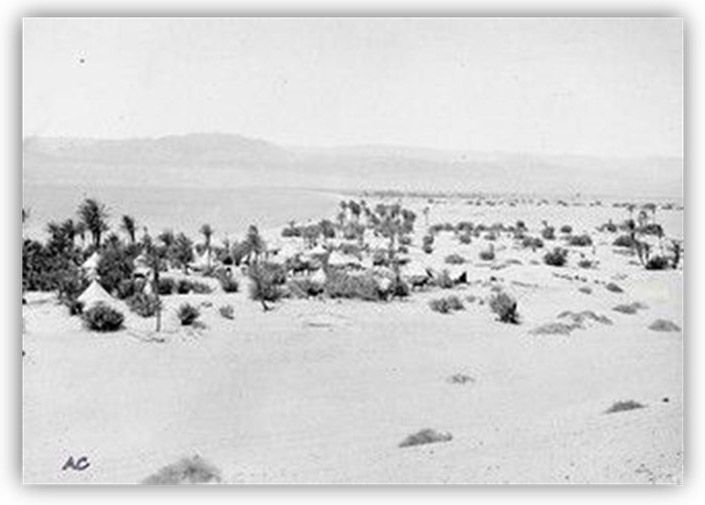

The movie is, of course, not entirely true. Instead of this famous scene of Lawrence leading the Arab troops in a massive offense,

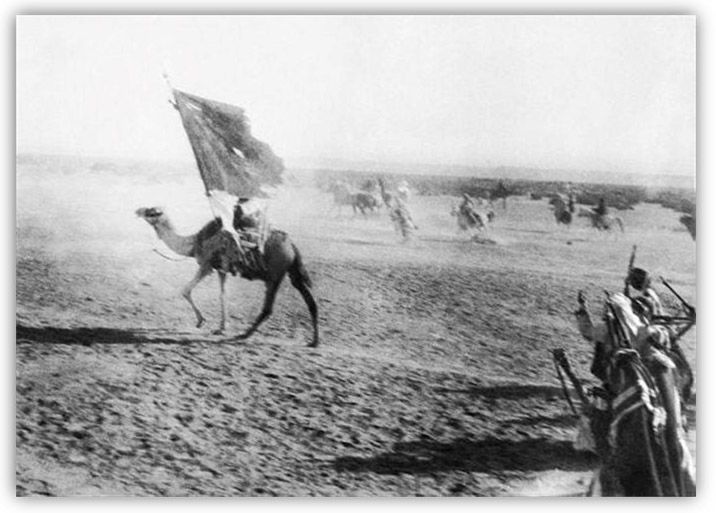

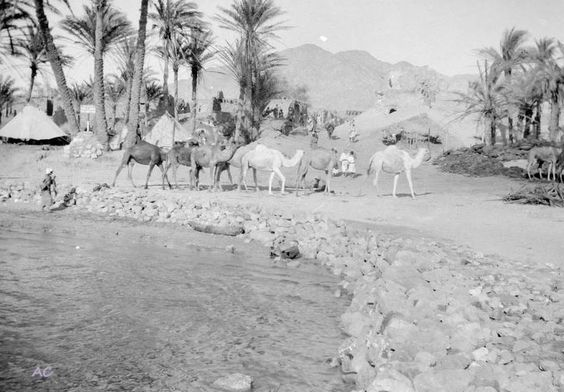

the reality was this actual photo of a few scraggly camels and their riders:

In fact, Lawrence accidentally shot his camel in the head and narrowly escaped injury in the fall. The real conflict took place two days earlier against the Ottoman position, not in the settlement of Aqaba.[16]

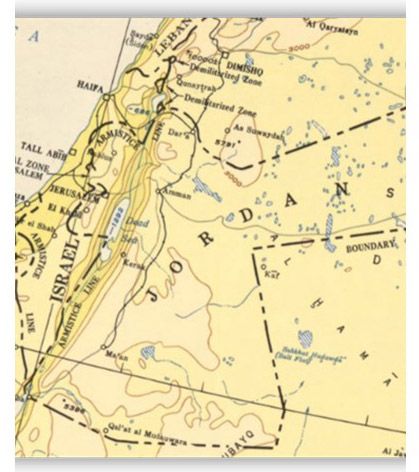

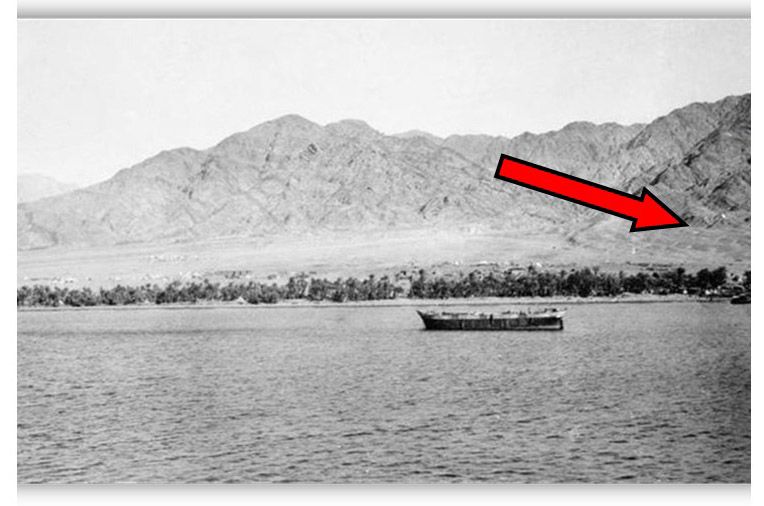

We live in the foothills of the peak where the red arrow is pointing.

SOVEREIGNTY

In 1915, the Hashemite kingdom leaders (from Saudi Arabia) created the Emirate of Transjordan. In September 1922, the British Mandate recognized Transjordan as a state, which remained under British supervision until 1946, at which time it became an independent country.[17]

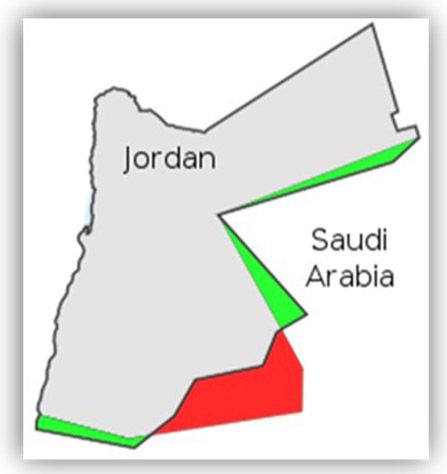

After World War I, Jordan fell under the influence of Britain, whose leaders drew the borders between Saudi Arabia and Jordan just outside the southern boundaries of Aqaba. Saudis didn’t agree with this division, but never took any action. Later on, in 1965, King Hussein traded 6000 square kilometers (2,316 square miles) of Jordanian desert for 12 km (7½ miles) of Saudi Arabian coastline south of Aqaba, where all of the snorkeling and diving takes place today. With the growing city and tourism in the region, this proved to be a very good deal for Jordan, which increased its total coastline to 27 km (16.8 miles).[18]

AQABA’S PRESENT-DAY CULTURE

From a population of 70,000 in the late 1990s, and a street system that was mostly unpaved, Aqaba has exploded into the twenty-first century. In our neighborhood alone, a dozen four-story apartment buildings are in progress. There were no street addresses until the last decade, but even though each building has a number now and each street a name, old ways die hard. Virtually no one uses or even knows what street they live on. Directions are by landmark … or GPS. It's inefficient in one way and high-tech in another.

From our point of view, Aqaba resembles the 1950s with some twenty-first-century gadgets and western culture mixed in. You may understand better when I say, it’s like someone who is sixteen years old going on twenty-one. The culture is only a couple of generations beyond camels for transportation and tents for housing. Even today, we sometimes see a herd of camels plodding along the highway at the edge of town. Several months ago, a shepherdess drove her goats down the street in front of our apartment.

There is also a boom-town feel. Downtown there is always a traffic rush. Fast-food restaurants proliferate. The evening hours stretch long with shoppers, and kids play soccer in the streets in the cool of the night. There is plenty of hustle-bustle to give the sense of progress.

ATTRACTIONS IN AQABA

ASEZA (Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority) makes Aqaba a duty-free zone. As one website says, “The Aqaba Special Economic Zone was inaugurated in 2001 as a bold and timely initiative by the government of Jordan to ensure that Aqaba’s commercial and cultural prominence continues into the twenty-first century … as a regional hub for trade, tourism, and culture.[19] We’ll be writing about it in depth in a future blog.

You can find world-class diving and snorkeling, a near-perfect winter climate, and great hospitality, making it a desirable destination for tourists from many nations. Saudi Arabians come by the busload to shop in Aqaba’s malls. Even Jordanians consider it the country’s playground. The king has a palace here in addition to those in Amman.

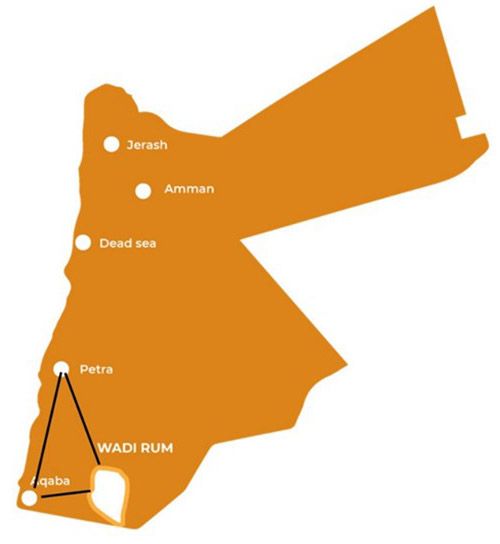

Of the three points of the Golden Triangle, Aqaba is the only big city. It’s "golden" because of the number of tourists coming to see the area’s beauty and history. From the Rose City of Petra’s stone-carved buildings, to the Martian landscape and crystal-clear star-gazing of Wadi Rum, plus the lure of Aqaba’s azure waters—the Golden Triangle is a magnetic attraction in Jordan, an important source of income for this resource-poor nation.

For more information on Jordan’s history, see our blogs, part 1 and part 2.

NOTE: The vintage black and white photos of Aqaba came from Pinterest. I could not find an original source for them.

[1] "Port expansion strengthens Jordanian city of Aqaba's position as modern shipping hub". The Worldfolio. Worldfolio Ltd. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

[2] Florian Klimscha (2011), Long-range Contacts in the Late Chalcolithic of the Southern Levant. Excavations at Tall Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan and Tall al-Magass near Aqaba, Jordan, archived from the original on 31 August 2021, retrieved 22 April 2016

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aqaba_Governorate. Accessed 10/06/2022

[4] https://www.viajordan.com/aqaba-history/. Accessed: 10/04/2022

[5] "The Beach of History (3700 BC to date)". aqaba.jo. AQABA. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

[6] "First purpose-built church". Guinness World Records. Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aqaba. Accessed 10/06/2022

[8] "The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago – Aqaba Project". Aqaba project. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2018

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aqaba. Accessed 10/06/2022

[10] Steven Runciman (1952). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East 1100-1187. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 186.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oultrejordain. Accessed 10/07/2022

[12] Ibid., Steven Runciman (1952). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East 1100-1187. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 356–357.

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Aqaba. Accessed 10/0/2022

[14] Bartholomew, J. G. (John George), 1860-1920, Palestine and Kerak (Transjordan) as shown in the 1922 edition of the Times Survey Atlas of the World, http://www.lunacommons.org/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~3143~450001:Asia-Minor,-Syria-&-Mesopotamia--Th (extract) https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~3143~450001:Asia-Minor,-Syria-&-Mesopotamia--Th, Public Domain,

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aqaba_Governorate. Accessed 10/06/2022

[16] Derek Davison, July 6, 2019, https://fx.substack.com/p/today-in-middle-eastern-history-the-332. Accessed 10/06/22

[17] https://www.viajordan.com/aqaba-history/. Accessed 0-22-2022

[18]10/05/2022, https://ctdots.eu/places/jordan/history-of-aqaba-jordan/. Accessed 10/06/2022

[19] https://aseza.jo/Pages/viewpage.aspx?pageID=1